aniTHeSi ha ammirazione per il grande architetto americano Antoine Predock, nato a Lebanon in Missouri il 24 giugno del 1936 e scomparso a Albuquerque il 2 Marzo 2024. Uomo del sud, aveva scelto di vivere e lavorare in New Mexico, una terra in cui il cielo è enorme tanto fisicamente che simbolicamente. E le sue architetture, bellissime, importanti, numerose, sono pensate per quel cielo. Amava il Pantheon, amava Constance DeJong, cui va tutto il nostro affetto, amava molto anche le motociclette che usava correndo per inalarlo quel cielo.

English text below

Architecture is a ride – a physical ride and an intellectual ride

Antoine Predock

Era il 1969 e nelle sale cinematografiche usciva un film che avrebbe cambiato l’immaginario collettivo degli anni a venire: Easy Rider. La pellicola, simbolo della New Hollywood, era molto più di un semplice racconto, era lo spaccato di una nuova gioventù, quella della protesta e dell’amore libero, che cercava nel viaggio e nell’immensità del paesaggio americano le chiavi per sconfiggere il senso di oppressione che il mondo degli “yes man” del capitale imponeva loro.

“Ah sì, è vero: la libertà è tutto, d’accordo… Ma parlare di libertà ed essere liberi sono due cose diverse. [… ] ti parlano, e ti riparlano di questa famosa libertà individuale; ma quando vedono un individuo veramente libero, allora hanno paura.” (Easy Rider: dialogo tra Billy e George Hanson)

Fig. 1 Ritratto di Antoine Predock

Classe 1936, e vincitore dell’AIA (American Institute of Architects) golden medal nel 2006, Prix de Rome all’Accademia American di Roma nel 1985, Antoine Predock è un viaggiatore, uno di quelli che la generazione di Easy Rider l’ha vissuta sulla propria pelle. È un centauro, un architetto che appena può salta su una delle sue molte moto e percorre centinaia di chilometri sulle highway americane, o sulle montagne del New Mexico Predock vive un rapporto simbiotico col paesaggio, ama il sapore della terra dei deserti del Sud che passa attraverso la bandana che protegge il volto, lasciando in bocca un sapore acre fatto di storia e paesaggi selvaggi.

Antoine è stato un asindrome’ di chi scrive sin dal dottorato di ricerca. Mi appassionai così tanto al suo lavoro che provai a contattarlo su Facebook per saperne ancora di più dato che i libri a lui dedicati non mi bastavano più. Con mia sorpresa, rispose e accettò di farsi intervistare per soddisfare la mia curiosità di ricerca. Mi raccontò della sua passione per Roma, che per lui e sua moglie era una città magica dove poter scoprire l’essenza dell’architettura, e di una ossessione per il Pantheon che aveva disegnato più e più volte nei suoi taccuini. Ci teneva Antoine a sottolineare come il viaggio per un’architetto fosse una fonte inesauribile di scoperta, un modo per entrare in connessione diretta con l’architettura che, nella sua visione, era al tempo stesso spirituale, simbolica e contestuale. Uno dei viaggi di cui era più orgoglioso era un folle giro in lambretta da Genova a Parigi fino ad Istanbul. Raccontava spesso del suo comprendere lo spazio attraverso la velocità delle due ruote che lasciavano spazio allo sguardo di esplorare e di perdersi oltre la linea dell’orizzonte e di comprendere lo scorrere del tempo nelle sequenze del paesaggio.

Fig. 2 Il Pantheon – schizzi di viaggio

Parlando con Antoine capì come la sua architettura altro non fosse che l’impersonificazione di se stesso: anche la sua architettura non si può comprendere da un punto di vista statico, da un piedistallo separato dalla dimensione terrestre; va invece esplorata, vissuta e attraversata, percepita nella sua matericità, nel rapporto intimo che intesse con il suolo e nelle sue spazialità perché la sezione è l’elemento principe di una investigazione che trova nella verticalità la propria ragione d’essere. Ancora studente a New York, mi disse, fu coinvolto nell’arte della danza e tradusse il movimento del corpo in elementi spaziali all’interno della sua architettura sia come una forte componente processionale che come focus sull’accumulo di punti di vista.

Il suo è un costruire che rifugge le mode, che definisce sequenze spaziali in orchestrazione con la psicologia del fruitore, che vuole porsi come elemento attrattore e custode di un’esperienza individuale e collettiva attivando un transfert attivo con la comunità con la quale entra in relazione. Le forme delle sue architetture, che definiva “quasi primordiali’, mostrano un forte legame con la geologia e un imprinting che affonda le sue radici nella quiete delle montagne isolate nel deserto e lentamente accarezzate dal vento.

È un’architettura tra “cielo e terra” dove l’edificio è il momento culminante di un percorso processionale in cui il fine ultimo dell’architettura è quello di creare informazione e, proprio come le tepee indiane, “di estrapolare un punto di riferimento nel caos del cosmo” come ci diceva il nostro coordinatore del dottorato. Non sono costruzioni nate per ‘riparare’, ma per cercare una connessione tra la sfera celeste e la terra, tra gli astri e quel vassoio infinito che è il deserto americano per orientarci in un orizzonte infinito.

Le sue oltre 230 opere sono caratterizzate da una varietà formale che rifugge dal raffreddarsi in uno stile o in una poetica rassicurante e facilmente replicabile e si fondano su una ricerca continua, un sporcarsi le mani del maestro che fornisce soluzioni specifiche a problemi generali e non viceversa. Come da lui stesso affermato, l’architettura è più di un momento fugace nella mente di un designer. Un edificio ha una vita tutta propria, che assume una qualità magica grazie alle cose che accadono prima, durante e dopo la sua concezione originale. Ed è quello che trasmettono molte delle sue costruzioni più conosciute e poetiche.

Nell’American Heritage Center and Art Museum (Laramie, WY, 1986 – 1993) scopriamo una delle componenti fondamentali del suo intendere l’architettura: Predock unisce alla sua attitudine compositiva la volontà di inserire nell’edificio surreali elementi icastici, che richiamano figure altre come la torre o la tenda (tepee) dei nativi americani. L’uso di una forma conica isolata, su una vasta distesa popolata dal nulla, se non da rari segni antropici, fornisce all’architettura una forte componente simbolica, magica. Qui, l’asse verticale del cono è occupato da un camino monumentale, fuori scala, che percorre l’edificio in tutta la sua altezza. Lo spazio interno è frutto di un lavoro di sezione, e un’illuminazione zenitale che, attraversando tutta l’altezza dell’edificio, scende lungo tutto lo scultoreo camino.

Fig. 3 American Heritage Center and Art Museum – il grande volume cavo – esterno/interno

Il complesso si articola attorno a quello che egli stesso definisce il rendezvous axis – l’asse degli incontri – un epicentro poetico dove l’architetto fa rifluire l’eredità degli incontri tra i native americani, i cacciatori francesi e gli esploratori europei. Il legno è uno degli elementi principali della struttura e nelle prospettive verticali e nei forti accenti chiaroscurali contiene echi di kahniana memoria. La dirompente forza verticale del comporre di Antoine Predock è riconoscibile nelle rotazioni di 45° di ogni livello rispetto all’asse centrale al fine di condurre il visitatore con un ritmo crescente verso il grande fascio di luce del lucernario superiore. Da uno spazio meandrico sotterraneo l’architetto scava la terra fino a spingersi a risalire verso il cielo spinti da una costante tensione ad uscire all’esterno, ad abbandonare le braccia della Madre Terra per protenderci verso le stelle.

Il terreno non è quindi un vassoio illimitato su cui poggiare oggetti-scultura, ma qualcosa a cui radicarsi, da scavare ed erodere per generare spazio e poesia.

Il rapporto con il terreno è proprio il motivo generatore dell’Arizona Science Center (Phoenix, Arizona, 1990 – 1997). Qui, sebbene il complesso si trovi nelle maglie della città edificata, sembra quasi ritrovarsi in un territorio desertico dove suggestioni derivanti da una matrice geologica generano spunti per la risoluzione di complesse problematiche urbane. La lama rivestita in metallo è uno sfondo per le altre figure del complesso e, in certe condizioni climatiche, sembra quasi dissolversi per lasciar spazio alla forza dei singoli volumi del calcestruzzo. In un clima così torrido i vuoti tra i solidi generano dei canyon dove trovar frescura nelle stagioni calde. Gli spazi interni si articolano in una dantesca discesa e risalita verso la luce, in una Divina Commedia filtrata dall’animo americano.

I volumi che compongono l’opera non intendono concorrere con il paesaggio circostante in un rapporto figura-sfondo ma generano una tensione che porta alla fusione di entrambi in un dittico figura-figura dove la presenza del cielo si lega alla terra attraverso la grande lama e mitiga il forte attacco al cielo della città di Phoenix dovuto ai grattacieli circostanti. Il complesso appare come una grande mesa (una superficie rocciosa dalla cime piatta e le pareti molto ripide dovuto ad erosione differenziale) che l’architetto fa riemergere dalle profondità della terra come ricordo mai sopito del tempo ‘antecedente all’uomo’.

Quando mi raccontava delle sue opere, Antoine spesso mi suggeriva che per comprenderle a fondo non bastava studiarle; bisognava entrare in connessione con quell’irrequietezza di fondo che lo permeava, quella sua spinta interna al viaggio e all’esplorazione, allo spostare sempre di un punto l’orizzonte da inseguire. E pian piano capì quello che stava tentando di dirmi, di come stava cercando di trascinarmi assieme a lui all’interno di uno degli dati fondativi della sua cultura e del suo paese: il mito della frontiera.

Predock è, infatti, un cittadino americano, discendente di coloro che, arrivando in terre così selvagge, partirono con il proprio carro alla ricerca di un proprio angolo di paradiso; ha nel sangue l’idea della scoperta e di un poter capire il mondo circostante solamente muovendosi nello spazio. È un modo nomade di vivere lo spazio dove l’architettura esiste come una stazione di sosta nell’infinito orizzonte, come un modo di estrapolare un granello di informazione dalla miriade di stelle nel cielo.

È per questo motivo che trovo poetico e chiarificatore il racconto di chi, collaborando nei primi anni Ottanta con lui, lo ricorda camminare nei siti di progetto e modellare con le proprie mani la creta di un plastico ogni qual volta l’orografia del terreno stuzzicava la sua fantasia e ogni volta che, mentre parlava di terra, arte e stelle, tracciava sul suo taccuino una linea che univa cielo e terra per richiamare una antica fusione tra il luogo e chi lo abita.

In occasione della scomparsa di Antoine Predock, antiTHesi rende disponbile per il free domwnload la monografia di Ppierluigi Fiorentini, Antoine Predock Echi nel deserto, Universale di Architettura, Marsilio Venezia 2007

English Text

antiTHeSi has admiration for the great American architect Antoine Predock, born in Lebanon, Missouri on June 24, 1936, and passed away in Albuquerque on March 2, 2024. A man of the South, he had chosen to live and work in New Mexico, a land where the sky is vast both physically and symbolically. And his beautiful, important, and numerous architectures were designed for that sky. He loved the Pantheon, he loved Constance DeJong, to whom all our affection goes, he also loved motorcycles very much, which he used to ride to breathe in that sky.

Architecture is a ride – a physical ride and an intellectual ride. (Antoine Predock during a 2005 podcast held at The American Institute of Architects (AIA))

It was the year 1969, and in movie theaters, a film was released that would profoundly alter the collective imagination of the years to come: Easy Rider. This cinematic work, emblematic of the New Hollywood movement, transcended its role as a mere narrative, constituting a snapshot of a new youth culture characterized by protest and free love. Far more than a simple story, the film served as a cross-section of a generation seeking, through travel and the vastness of the American landscape, the keys to overcoming the pervasive sense of oppression imposed upon them by the conformist world of capitalistic “yes men.”

“Oh yes, it’s true: freedom is everything, agreed… But talking about freedom and being free are two different things. […] They speak to you, and they keep talking to you about this famous individual freedom; but when they see someone truly free, then they are afraid.” (Easy Rider: Dialogue between Billy and George Hanson)

Born in 1936 and recipient of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Golden Medal in 2006, Antoine Predock is a traveler, one who experienced the era of Easy Rider firsthand. He is a centaur, a figure who eagerly mounts his faithful companion to traverse hundreds of kilometers on the American highways. Predock maintains a symbiotic relationship with the landscape, cherishing the taste of the earth in the Southern deserts that permeates through the bandana protecting his face, leaving a bitter flavor in the mouth composed of history and untamed scenery.

Antoine has been a sort of personal fascination for me since my doctoral research. I became so engrossed in his work that I attempted to contact him via Facebook to delve deeper into his insights, as the existing literature dedicated to him no longer sufficed for my curiosity. To my great surprise, he responded and agreed to be interviewed, satisfying my research-driven inquisitiveness. He shared his passion for Rome, a city he considered magical, where he and his wife could unravel the essence of architecture. He also revealed an obsession with the Pantheon, a structure he had sketched repeatedly in his notebooks. Antoine emphasized the inexhaustible fount of discovery that travel represents for an architect—a means to establish a direct connection with architecture that, in his vision, was simultaneously spiritual, symbolic, and contextual.

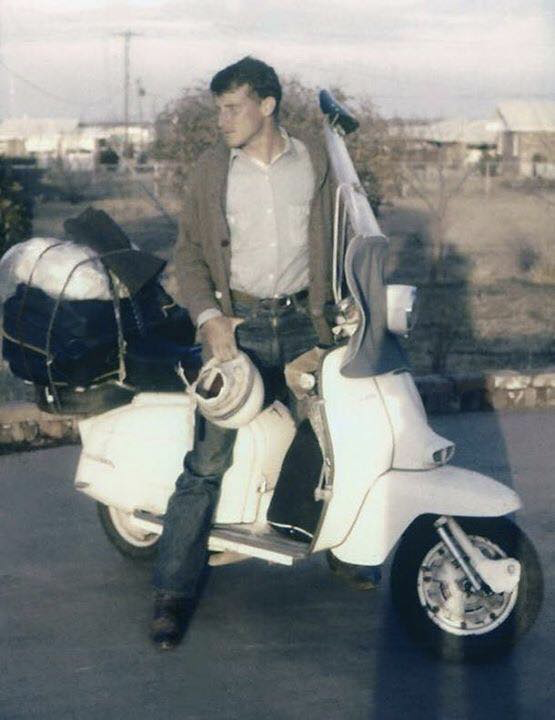

One of the journeys of which he was particularly proud involved a daring Lambretta ride from Genoa to Paris and onwards to Istanbul. Antoine often recounted how he perceived space through the speed of the two wheels, allowing his gaze to explore and lose itself beyond the horizon. Understanding the passage of time unfolded through the landscape sequences, marking one of the many dimensions he cherished in the architectural experience.

Image. 4 Antoine Predock during the 1960s on the Genoa-Paris-Istanbul Tour

In conversing with Antoine, I came to understand how his architecture was nothing more than the reification of himself: it cannot be grasped from a static standpoint, detached from terrestrial dimensions; it demands exploration, living, and traversal. One must perceive its materiality, the intimate relationship it weaves with the ground, where the section becomes the principal element in a spatial investigation that finds its raison d’être in verticality. Still a student in New York, he recounted being engaged in the art of dance, translating the body’s movement through space into spatial elements within his architecture, serving as a strong processional component and a focal point on the accumulation of perspectives.

His construction approach shuns trends, defining spatial sequences orchestrated with the psychology of the user, aspiring to be an attractive element and custodian of an individual and collective experience by actively engaging with the community. His forms, at times self-described as ‘primordial,’ exhibit a strong connection with geology and an imprinting rooted in the tranquility of mountains isolated in the desert, gently caressed by the wind.

It is an architecture between “heaven and earth,” where the building is the culmination of a processional journey, and the ultimate goal of architecture is to create information and, much like Indian tepees, extract a reference point from the chaos of the cosmos. These constructions are not born to ‘shelter’ but to seek a connection between the celestial sphere and the earth, between the stars and the infinite canvas of the American desert, helping us orient ourselves in an infinite horizon.

His more than 230 works are characterized by a formal variety that resists crystallizing into a style or easily replicable poetics, grounded in continuous research—a hands-on approach by the master providing specific solutions to general problems, not vice versa. As he stated, architecture is more than a fleeting moment in a designer’s mind. A building has a life of its own, acquiring a magical quality through events that transpire before, during, and after its original conception. This essence is conveyed by many of his best-known and most poetic constructions.

At the American Heritage Center and Art Museum (Laramie, WY, 1986 – 1993), we encounter one of the fundamental components of Antoine Predock’s architectural philosophy. Predock combines his compositional expertise with the intention to incorporate surreal, iconic elements into the building, reminiscent of other figures such as the tower or the tepee of Native Americans. The use of an isolated conical form on a vast expanse populated seemingly by nothing but sporadic anthropic signs imparts a strong symbolic and magical quality to the architecture.

The vertical axis of the cone is occupied by an out-of-scale monumental chimney that traverses the entire height of the building. The internal space is a result of meticulous sectional work, featuring zenithal lighting that, streaming through the entire height of the structure, flows along the sculptural axial chimney.

The complex is structured around what Antoine Predock himself defines as the “rendezvous axis“—a poetic epicenter where he channels the legacy of encounters between Native Americans, French hunters, and European explorers. Wood constitutes one of the primary elements of the structure, and in the vertical perspectives and strong chiaroscuro accents, it holds echoes of a Kahnian memory. The compelling vertical force in Predock’s composition is recognizable in the 45° rotations of each level relative to the central axis, aiming to guide the visitor with an increasing rhythm towards the expansive beam of light from the upper skylight. From an underground meandering space, the architect excavates the earth, ascending towards the sky driven by a constant tension to emerge outside, to leave the embrace of Mother Earth and reach towards the stars. The terrain is not an unlimited tray on which to place sculpture-like objects but something to anchor oneself to, to dig into and erode, generating space and poetry.

The relationship with the ground is precisely the generative theme of the Arizona Science Center (Phoenix, Arizona, 1990 – 1997). Here, although the complex is embedded within the urban fabric, one almost feels transported to a desert terrain where suggestions stemming from a geological matrix offer insights for resolving complex urban issues. The metal-clad blade serves as a backdrop for the other elements of the complex and, under certain climatic conditions, seems to dissolve, making way for the force of the individual concrete volumes. In such a scorching climate, the voids between the solids create canyons where one can find relief during the hot seasons.

Image 5 “Arizona Science Center – Overview of the Complex and Sky-Ground Relationship Within”

The internal spaces unfold in a Dantean descent and ascent towards the light, in a Divine Comedy filtered through the American spirit.

The volumes that compose the work do not aim to compete with the surrounding landscape in a figure-background relationship but generate a tension that leads to the fusion of both into a diptych of figure-figure. The presence of the sky is bound to the earth through the grand blade, mitigating the strong assault on the sky from the surrounding skyscrapers of the city of Phoenix. The complex appears as a vast mesa (a flat-topped rocky formation with steep sides due to differential erosion), which the architect brings forth from the depths of the earth as an ever-present reminder of the ‘pre-human’ time.

When Antoine spoke to me about his works, he often suggested that to truly understand them, studying was not enough; one had to connect with that underlying restlessness that permeated him, the internal drive for travel and exploration, the refusal to stay still but always to shift the horizon to pursue. Slowly, I grasped what he was trying to convey, how he sought to pull me alongside him into one of the foundational imprints of his culture and one of the foundational myths of his country: the myth of the frontier.

Indeed, Predock is an American citizen, descended from those who, arriving in such wild lands, set out with their wagons in search of their corner of paradise. The idea of discovery and understanding the surrounding world only by moving through space runs in his blood. It is a nomadic way of living space where architecture exists as a rest stop in the infinite horizon, a means of extracting a grain of information from the myriad stars in the sky.

This is why I find it poetic and enlightening to hear stories from those who collaborated with him in the early 1980s, recalling him walking through project sites and shaping clay models by hand whenever the topography of the land sparked his imagination. Poetically, he would draw a line in his notebook connecting the sky and the earth, evoking an ancient fusion between the place and its inhabitants.

Image. 6 Portrait of Antoine Predock on a Motorcycle in the Desert (2005)

On the occasion of Antoine Predock’s passing, antiTHesi makes available for free download the monograph by Pierluigi Fiorentini, “Antoine Predock: Echi del deserto” (Antoine Predock: Echoes in the Desert), published by Universale di Architettura, Marsilio Venezia 2007.